JEFF’s TOP 30 FILMS

1. City Lights, (1931) by Charlie Chaplin

In 1928, as theaters across the country converted to synch-sound projection, Chaplin began production on a film that would defy the trend and demonstrate the virtue of his pre-talky cinematic artform. It took three years under his perfecting standards, and the result is nothing less than magnificent.

2. Grand Illusion, (1937) by Jean Renoir

With this film, Renoir reveals how bound we are by the illusions of national identity, even when class and mutual suffering trump such ideological sentiment within interpersonal relations. Yet, as with the best of Renoir’s work, whatever our ambitions and sense of cultural or historical relevance, it is the inevitable shifts of time that humble us in the end.

3. The Lady Eve, (1941) by Preston Sturges

A stunning number of comedy masterpieces came out of Hollywood in the early 1940s: Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940); Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story (1940); Hawk’s His Girl Friday (1940) and Ball of Fire (1941); the obscure and underappreciated WC Fields’s gem, Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941); Lubitsch’s To Be or Not To Be (1942); Stevens’ The More the Merrier (1943); Wellman’s Roxie Hart (1942), which Kubrick listed early in his career with WC Field's’s The Bank Dick (1940) among ten films that impressed him; and an impressive number of other Sturges films in short succession—Sullivan’s Travels (1941), The Palm Beach Story (1942), The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, and Hail the Conquering Hero (both 1944). But The Lady Eve tops them all for my taste with its beautiful construction, flawless performances, glowing chemistry, sharp dialogue, and hilarious pratfalls. It’s the film I’ve seen more than any other.

4. Seven Men From Now, (1956) by Bud Boetticher

I’ve reluctantly passed on choosing one of the more obvious Western masterpieces, namely Stagecoach (1939), Rio Bravo (1959), Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), or Ulzana’s Raid (1972) to go with a lesser-known film, the first of a handful of tightly-written, low-budget indie collaborations between director Boetticher, screenwriter Burt Kennedy, and star Randolph Scott. In Scott’s portrayals, we get a clear alternative to the archetype of the American man of the West, distinguished by stoic poise rather than the more popular John Wayne gung-ho swagger. The film resolves with my favorite showdown in cinema as Scott faces off with Lee Marvin in a scene pared down to its essence, playing almost zen-like in its formal construction.

5. Street of Shame, (1956) by Kenji Mizoguchi

My favorite Mizoguchi film is his last, a masterclass of ensemble storytelling that guides the eye through complex compositions involving chiaroscuro, deep focus, simultaneous foreground-background action, and precise blocking.

6. Nights of Cabiria, (1957) by Federico Fellini

My all-time favorite performance: Giulietta Masina as Cabiria.

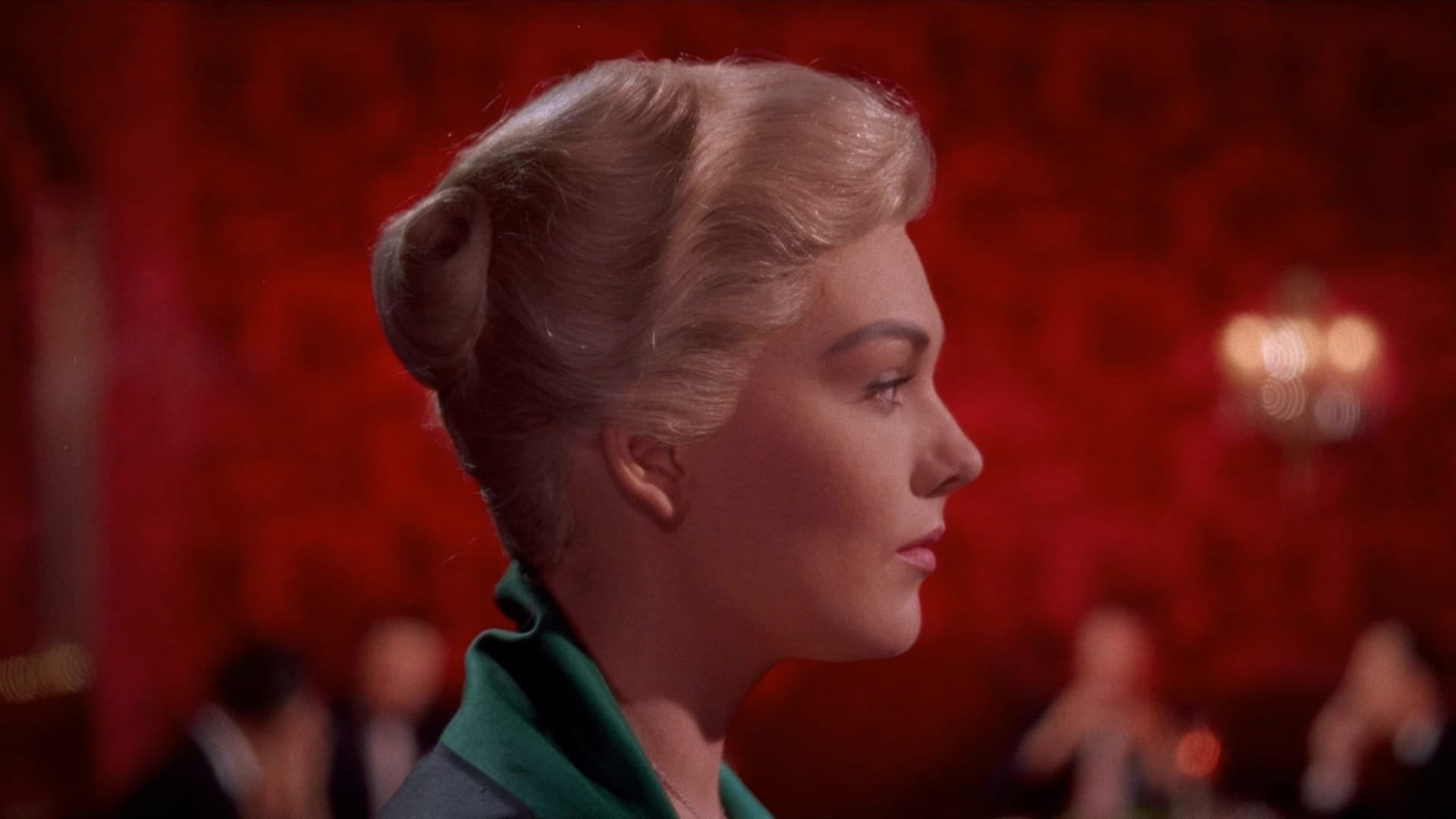

7. Vertigo, (1958) by Alfred Hitchcock

Vertigo is a multi-layered modern adaptation of the Orpheus myth that would otherwise seem preposterous if not framed within the context of James Stewart’s subjective infatuation with a dream girl and his subsequent desperate attempt to resurrect her from the dead.

8. Floating Weeds, (1959) by Yasujiro Ozu

The profound experience of an Ozu film occurs residually, like an aftertaste lingering long after the lights go on. Very few films have that lasting effect and Ozu has a dozen or more of them.

9. The 400 Blows, (1959) by François Truffaut

Still the greatest depiction of adolescence as a stiff-lipped rebellion against neglect at home, injustice at school, and the overall stricture of his youthful impulses.

10. Eyes Without a Face, (1960) by Georges Franju

This is my favorite horror film, sitting just a hair above John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and Tod Browning’s The Unknown (1927, starring Lon Chaney and a young Joan Crawford).

11. La Jetée, (1962) by Chris Marker

Rarely do films defy the normal modes of expression to such profound and singular effect. La Jetée takes an incredibly spare approach, conveying a tightly-written meditation on time, memory, and loss, in the form of a science-fiction slide-show parable.

12. Winter Light, (1963) by Ingmar Bergman

I love Bergman’s chamber dramas, and this is my favorite, a cinematic pinnacle of complex thematic layering and precise choreography of performance to the composition.

13. Charulata, (1964) by Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray’s films remain particularly dear to me, particularly The Apu Trilogy (1955, ‘56, and ‘59), The Music Room (1958), and Days and Nights in the Forest (1970), but it was Charulata that won my heart forever in the scene in which Soumitra Chatterjee sings, “Ami Chini Go Chini Tomare” to Madhabi Mukherjee.

14. Diamonds of the Night, (1964) by Jan Nemec

Unavailable in the West for decades except in bootleg form, Diamonds of the Night is a little-known 65-minute feature film from the Czech New Wave that desperately needed rediscovery and preservation. The Criterion Collection answered my prayers in 2018, beautifully restoring the film and making it available to stream on their online channel. Its premise is of two Jewish boys who wander through a dark wood, cold and hungry, after escaping from a train on its way to a concentration camp. As one of the nameless boys follows the other toward an uncertain fate, his memories, daydreams, and hunger-induced hallucinations gradually blend with his journey, progressing quietly toward its haunting, transcendental end.

15. Le Bonheur, (1965) by Agnes Varda

My favorite Agnes Varda film, this satire of a man’s unaffected happiness, subverts the idylls of impressionism to stunning and critical ends. Remarkably sly, Varda’s technique presents a man’s infatuation as a gauzy filter upon the world, in which the object of his attention is like a blooming flower in a lush garden. Perfect and sensual when first sighted, she becomes a mere accent in the decor of his domestic sphere, once he’s plucked and placed her there. It’s a conspicuously soft look on a disturbing subject, which makes it all the more effective and engaging as a work of art. The flirtation scene between Francois and Émilie at the bistro remains one of my favorite sequences of cinematic choreography.

16. Au Hasard Balthazar, (1966) by Robert Bresson

Bresson hit several high points of transcendental cinema with this film and others, including Diary of a Country Priest (1951), A Man Escaped (1956), and Pickpocket (1959).

17. Chinatown, (1974) by Roman Polanski

An exemplar of the hard-boiled detective noir in the Chandler tradition, Jake Gittes’s convoluted investigation begins with a sense of indignity, widens into suspicion of political conspiracy, and then narrows into a shocking personal revelation of family abuse, ultimately depicting a landscape so wholly suspect and corrupt that virtue can only reside in our hero’s underlying moral integrity and honorable intentions, even if his actions lead inevitably to tragedy. Other Chandleresque favorites include L.A. Confidential (1997), The Big Lebowski (1998), and Inherent Vice (2014).

18. Mirror, (1975) by Andrei Tarkovsky

Mother as muse. Film as a mirror. Along with Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes (1992), this is a prime example of that rare genre, poetic memoir.

19. Barry Lyndon, (1975) by Stanley Kubrick

My pick for the greatest film of all time, reaching artistic heights in its dramatic scope, tonal balance, composition, thematic interests, and overall achievement.

20. Serie Noire, (1979) by Alain Corneau

I recently discovered this film while browsing letterboxd.com for adaptations of my favorite pulp crime authors, including Charles Willeford, Richard Stark (aka Donald E. Westlake), Elmore Leonard, and George V. Higgins. I’ve always felt the Jim Thompson crime novels (and adaptations in turn) offered wholly original characters and exciting setups, but were somehow deficient in their ambiguous unspooling of the main characters’ psychological states. And unlike Philip K. Dick’s work, no director had managed to realize the work’s potential in a cinematic form. Serie Noire is a clear exception. It’s a perfect meld of tone and style, largely due to the inspired casting, especially Patrick Dewaere’s virtuosic performance as the protagonist, Franck. Other favorite gems of pulp crime include Andre De Toth’s Crime Wave and Samuel Fuller’s Pickup On South Street (both 1953), the Coen brothers’ Fargo (1996), and my favorite Tarantino film, Jackie Brown (1997, sublimely adapted from Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch).

21. L’Argent, (1983) by Robert Bresson

With an extreme distillation of his original style, Bresson divested the plot of its usual spiritual preoccupations, allowing grace to arise out of something even more inscrutable, as if in spite of its bleak outlook.

22. Full Metal Jacket, (1987) by Stanley Kubrick

The greatest depiction of soldiers at war explores the dilemma of their role as killers without inadvertently glorifying their actions or sentimentalizing their purpose as a fight for some greater good.

23. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, (1988) by Pedro Almodovar

While David Lynch draws from soap operas to imbue his noir films with a distinct dream-narrative quality, Almodovar draws from Spanish soap operas for his particular brand of vibrant melodramatic and often comedic thrillers. This is my favorite of his, among Tie Me Up! Tie me Down! (1989), Talk to Her (2002), and The Skin I Live In (2011).

24. Total Recall, (1990) by Paul Verhoeven

Total Recall holds up surprisingly well with its mindblowing sci-fi premise, exciting plot developments, impressive practical world-building and FX, thrilling performances, badass action, and unbeatable Arnie one-liners. Like Jaws (1975), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), The Road Warrior (1981), Back to the Future (1985), Aliens (1986), Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991), Minority Report (2002), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), it has everything I could want in a pure popcorn thriller/action flick.

25. A Summer’s Tale, (1996) by Éric Rohmer

Of the French New Wave filmmakers, I prefer two older, late-comers to the scene, Rohmer and Pialat, particularly the latter’s We Won’t Grow Old Together (1972). A Summer’s Tale is one of many favorites of Rohmer’s, amongst La Collectionneuse (1967), My Night at Maud’s (1969), The Aviator’s Wife (1981), Pauline at the Beach (1983), Full Moon in Paris (1984), The Green Ray (1986), Boyfriends and Girlfriends (1987), and A Tale of Winter (1992).

26. My Neighbors the Yamadas, (1999) by Isao Takahata

An underrated Ghibli masterpiece, a sublime series of domestic haikus.

27. The Fog of War, (2003) by Errol Morris

A surprisingly candid and profound reflection on the stakes of power.

28. The Wayward Cloud, (2005) by Tsai Ming-Liang

My favorite from the Taiwanese New Wave is this cinematic meditation on loneliness and longing.

29. No Country For Old Men, (2007) by the Coen Brothers

A supreme adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s made-for-cinema novel.

30. The Souvenir, (2019) by Joanna Hogg

My favorite film of the 21st century so far is this reflexive, non-judgmental depiction of an intimate relationship and its ineffable spell, both toxic and compelling, on the filmmaker’s life and art.